Breaking News on Primary Care

A Brief Guide to the New CMMI ACO and Care Delivery Demonstrations: Discerning the Opportunities for Primary Care

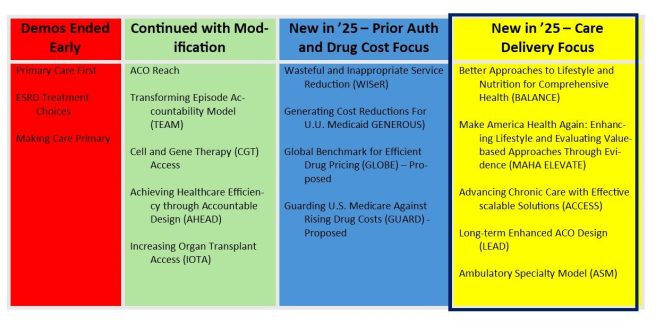

2025 was a busy year for the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), the agency within CMS that develops and tests promising new healthcare payment and service delivery models for their ability to improve quality, reduce unnecessary cost, and improve patient experience. CMMI ended some demonstrations early, modified components of other demonstrations, and launched an array of new demonstrations – ten in the past two months alone. Some of these new demonstrations focus on prior authorization and drug pricing, but of special focus to those interested in primary care and population health are those rooted in care delivery.

Taken as a whole, it appears that CMMI is signaling interest in making sure that model designs will produce their intended end goals such as cost savings. And as we’ve seen across administrations, the commitment to value-based payment and beneficiaries in accountable patient and clinician relationships is here to stay. So is aligning financial incentives so that multiple healthcare partners who are caring for a beneficiary provide efficient, effective care throughout a beneficiary’s care journey. There is also an intentional focus on chronic disease prevention and management focus woven into expectations and approaches.

Let’s take at each of the new care delivery-focused models (BALANCE, MAHA Elevate, ACCESS, LEAD, and the ASM) with a focus on how each impacts primary care and population health. Note that CMMI has yet to release additional details and application material for some of the models. Still, it is helpful to understand the basic parameters of each new model to gauge their applicability and interest in your work serving patients.

- Better Approaches to Lifestyle and Nutrition for Comprehensive Health (BALANCE) aims to increase access to select GLP-1 medications and healthy lifestyle interventions for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries through CMS drug pricing negotiation on behalf of state Medicaid agencies and Medicare Part D plan sponsors. The intent is to make anti-obesity medications more affordable as a treatment option when appropriate. The program is expected to launch in 2027 with an early bridge component to the demonstration kicking off in mid-2026.

| BALANCE DEMO ROLE FOR PRIMARY CARE: No direct role or opportunity to participate in the demonstration, per se. The BALANCE demonstration and other initiatives may result in decreased pricing of GLP-1 medications for some patients. As well, all beneficiaries receiving GLP-1s for weight management under BALANCE are to be provided access to a lifestyle support program by the manufacturer at no cost. The lifestyle intervention is intended to offer education on how to maintain weight loss and make positive health choices to help improve health. |

- MAHA Enhancing Lifestyle & Evaluating Value-based Approaches Through Evidence (ELEVATE) Elevate is a three-year program aimed at reducing chronic disease progression by funding evidence-based functional and lifestyle medicine approaches, such as nutritional support and physical activity not covered by Original Medicare. Private practices, health systems, ACOs, academic organizations, community-based organizations and others will be eligible to submit an application detailing their proposed approach and approximately thirty awards will be made with a composite total of $100 million and a start date of September 2026.

| MAHA ELEVATE DEMO ROLE FOR PRIMARY CARE: No direct role unless you are affiliated with a larger organization that receives an award. Such practices may have the opportunity to support intervention implementation integration in patient care. |

- Advancing Chronic Care with Effective Scalable Solutions (ACCESS) is focused on reducing payment barriers to digital health tool use. On one hand, it is important to adapt to new innovations in patient self-management support and remote monitoring. On the other, for the many new tools that are emerging, it is sometimes difficult to discern between hype and demonstrated ability to support patient self-management of chronic disease.

ACCESS is a ten-year national voluntary demonstration of technology-supported care for early and late cardiometabolic and kidney conditions, musculoskeletal conditions, and behavioral health conditions, including depression or anxiety. There are expected to be outcomes-aligned payments from CMS to the selected technology vendors as well as some payment to the providers who are supporting patients using approved technologies in the demonstration.

Nationally, several payers have also signed up to align with the core concepts of the ACCESS model. So far, Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield, Blue Shield of California, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Minnesota, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Dakota, BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee, CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield, Centene, Cigna, CVS Health, Devoted Health, Guidewell, Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield of NJ, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare have indicated that they will do so. Though there are no Michigan-based payers in this set as of yet, adoption by multiple payers should help to reduce administrative burden and build volumes for scalable implementations. The ACCESS model includes a reporting infrastructure that incorporates a new health information standard called Fast Health Interoperable Reporting (FHIR). This means that not only is the demonstration a test of technology-supported care, it is also a test of interoperability feasibility and readiness in real-time. The model has a ten-year span with a start date of July 5, 2026.

| ACCESS DEMO ROLE FOR PRIMARY CARE: CMS will maintain a public directory of digital health tools approved in the ACCESS demonstration. Primary care practitioners will be able to refer patients, though patients will also be able to sign up directly with participating ACCESS organizations. Primary care clinicians will be able to bill a co-management payment to CMS (and potentially to other participating payers) for reviewing electronic updates and documenting related care coordination activities (e.g., medication adjustments, etc.) for ACCESS patients in the demonstration when they take an active role in oversight and coordination. |

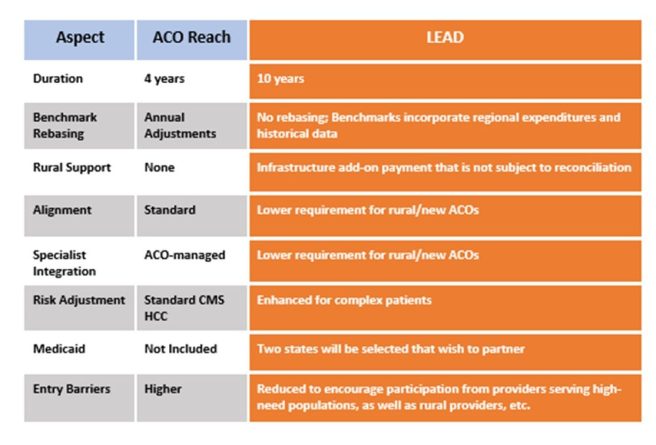

- Long-term Enhanced ACO Design (LEAD) is the long-awaited successor to ACO Reach. In LEAD, CMMI has worked to make ACO participation more feasible for smaller, independent providers and organizations serving underserved or complex populations. It is a ten-year voluntary model open to current ACO REACH participants, Medicare FFS providers who are new to accountable care, providers serving underserved populations including dual eligibles, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and Rural Health Centers (RHCs) as well.

There are two kinds of participants in LEAD: Participant Providers and Preferred Providers. Physicians and health care organizations that elect to be Participant Providers take direct accountability for cost and quality and drive beneficiary alignment. LEAD will use a whole Tax Identification Number (TIN) approach, which captures all National Provider Identifiers (NPIs) billing under a Participant TIN as Participant Providers.

Preferred Providers, on the other hand, take indirect financial accountability and do not drive beneficiary alignment or quality performance for the ACO, per se. For example, specialists and institutional providers (e.g., post-acute care) might be particularly drawn to Preferred Provider participation. Preferred Providers will be managed at the TIN-NPI level, with the intent of providing Participant Providers more specificity and flexibility in partnerships.

LEAD participants select one of two levels of risk-sharing: 1) Global risk with 100% upside or downside risk relative to the established performance benchmark, or 2) Professional risk with 50/50 gain or risk sharing depending on performance. There are a few design components in LEAD that make it especially interesting. For example, LEAD is designed with a goal of increasing stability in benchmarks. Unlike REACH ACO, LEAD will not have annual rebasing. In addition, the model offers the opportunity for beneficiary enhancements and incentives to encourage patient engagement.

In an attempt to reduce the complexity of building the entire array of partnerships necessary to care for ACO patients, CMS introduces CMS Administered Risk Arrangements (CARAs) that are intended to provide support to ACOs to enable episode-based risk arrangements between ACOs and their specialists and provider organizations to facilitate greater and stronger Preferred Provider relationships with these downstream health care providers. In these structures, CMS administers the arrangements and facilitates information sharing.

This will include common contracting frameworks by enabling export of episode information into contracting templates. These voluntary components facilitate digital data-sharing and payment among preferred providers, downstream specialists and provider organizations. CMS could then share episode data with ACOs and the Preferred Providers with whom they enter into episode-based risk arrangements (EBRAs).

LEAD not only extends the traditional time frame for demonstrations as it has a ten-year lifespan, but it also extends a bit beyond the Traditional Medicare population by working with two selected states to include Medicaid beneficiaries. CMS also tries to more fully adjust for the work involved in managing the care of complex patients. A comparison and contrast between ACO Reach and LEAD is shown below:

ACO Reach and LEAD ACO Comparison

Applications for LEAD participation are not out yet but expected to be released soon, as the application period opens in March 2026 with a model launch date of January 2027.

| LEAD ROLE FOR PRIMARY CARE: If you participated in REACH ACO or are new to accountable care, treat underserved populations including dual eligibles, are a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) or Rural Health Center (RHC), you may want to explore LEAD as a gateway to increase your experience with value-based, accountable care. Given the way that CMS has decreased barriers to entry for smaller providers and those that serve high-needs populations, for those new to accountable care two-sided risk arrangements, it may be hard to find a better opportunity to test the ACO waters. In either case, modeling the financial impacts when additional details and the demonstration are released at the LEAD website will be a good place to start. |

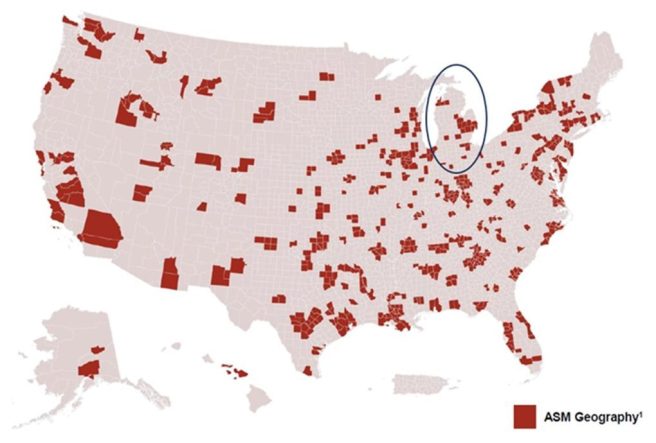

- The Ambulatory Specialty Model (ASM) reflects CMMI’s extension of two-sided risk beyond primary care and Accountable Care Organizations and into specialty outpatient care. Though the model is specialist-focused, participating specialists are required to establish Collaborative Care Arrangements (CCAs) with primary care providers to define shared roles, data-exchange expectations, and joint responsibility for patient management, including transitions between care settings.

The ASM is a two-sided risk payment model that will be mandatory in selected Core-Based Statistical Areas (CBSAs) for specialists who commonly treat Medicare beneficiaries for heart failure or low back pain in outpatient settings. In Michigan, the selected ASM areas will be: Flint, Jackson, Kalamazoo-Portage, Midland, Owosso, Saginaw, Traverse City, and Warren-Troy-Farmington Hills. The other ASM regions shown below on the map are fairly well-distributed nationally.

The ASM aims to improve prevention and upstream management of chronic disease and is intended to produce reductions in avoidable hospitalizations and unnecessary procedures. Payment is based on performance relative to their peers which will determine the payment adjustment on their future Medicare Part B claims for covered services.

The model will begin on January 1, 2027 and run for five performance years through December 31, 2031. Many think that it is likely that over time, CMMI may add more conditions and specialties into the model design.

| ASM ROLE FOR PRIMARY CARE: Though model participants are specialists who treat patients with heart failure and low back pain, these providers will be required to establish a formal relationship with at least one PCP. This allows for tighter integration between PCPs and specialists in the management of specific, high-cost, high-volume conditions. |

The National Movement to Increase Investment in Primary Care

Primary care serves as the foundation of a well-functioning healthcare system. It can point patients in the right direction to improve their health status, manage existing conditions, and spot problems before they become serious. Across the country, more than 35% of healthcare visits are provided by primary care, yet it receives only 5% of health spending[1]. As a result of this underfunding, there are long wait times to see a primary care provider and missed opportunities to manage preventable disease exacerbations. There is a more efficient and effective way to spend our health care dollars by better resourcing primary care and there is a national movement afoot to bolster primary care.

Robust, widely available primary care is needed more than ever in Michigan. Even now, 25% of Michiganders lack a usual source of care. Looming losses in Medicaid coverage from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBA) and escalating premiums place an even greater strain on primary care. In addition to Michigan’s affordability and access challenges, the population of the state is growing sicker. Rates of frequent physical distress, low birth weight, multiple chronic conditions and obesity rates in Michigan now exceed the national average[2]. Of Michigan’s 83 counties, over 70 are designated by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) as Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs), areas with more than 3,500 people for every one primary care provider.

There is good evidence that robust, evidence-based primary care is cost-effective and improves population health, reducing the burden of chronic disease, lowering healthcare costs, and delivering patient satisfaction.[3] Areas with higher ratios of primary care physicians to population have lower costs of care and better health outcomes.[4] The strength of the evidence supporting the important role of accessible, effective primary care for patients has catalyzed action across the nation. More than a third of states have already passed legislation or enacted regulation to increase the percentage of spending that goes to primary care.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) 2021 report on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care: Rebuilding the Foundation of Health Care[5] provides a robust set of principles and recommendations for improving primary care. It emphasizes an integrated, whole-person health model of care that is delivered by an interprofessional team that partners with patients. This interprofessional team is comprised of a primary care physician who leads a team of health care professionals (e.g., NP/PAs, RN Care Managers, other nurses, medical assistants, and additional ancillary staff such as social workers, community health workers, and pharmacists, etc.) that focus on each patient’s health needs to design a patient care plan.

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s (CMMI’s) AHEAD demonstration is a federal model that increases investment in primary care as a part of a larger strategy to curb growth in overall health care costs, provide financial stability for hospitals, and support beneficiary connection to community resources. Six states (Maryland, Connecticut, Hawaii, Vermont, Rhode Island, and New York) participate in AHEAD so far. The model requires participation of the State, and a set of hospital partners. Thus far in Michigan, there has not been interest from the state or hospital partners in participating in AHEAD.

More than 20 states have taken action to increase investment in primary care, including some of the AHEAD states mentioned above. The way that states elect to define primary care spending varies, but for context, the latest version of the Primary Care Spending Dashboards released by the Milbank Fund show Michigan spending across all payer types for the narrow definition of primary care (i.e., payment to primary care physicians) at 5.5%.

Among the states that have passed legislation to increase investment in primary care are:

- California’s Health Care Affordability Board approved two related primary care investment benchmarks in October 2024: 1) a statewide investment benchmark of 15% of total medical expense (TME) allocated to primary care for all payers by 2034; and 2) an annual improvement benchmark of 0.5-1 percentage point per year increase in primary care spending as a share of TME for each payer for years 2025-2033. The Office of Health Care Affordability (OHCA) measures and reports on primary care investment, with the first public reporting scheduled for 2026. Though the benchmark is not enforceable, the hope is that plans will voluntarily meet targets. California also has a statewide health care spending target, set at 3.5% for 2025 and phasing down to 3.0% for 2029, which is enforceable.[6]. In addition, the state’s Medicaid program, Medi-Cal, increased rates for primary care services to 87.5% of Medicare rates, effective January 1, 2024.

- Delaware has set a primary care target of 11.5% of total medical spending by 2025 for private insurers and a requirement to match Medicare reimbursement rates for primary care[7]. However, a recent Delaware Primary Care Reform Collaborative strategic plan report[8] expressed concern about the extent to which Medicaid and commercial payers are meeting their expectations. Members of the state’s Primary Care Reform Collaborative noted at their August 2025 meeting that the state is exploring participation in the federal AHEAD model as a promising long-term option.

- Oregon’s strategy to increase primary care has been perhaps the nation’s most successful over time. In 2015, the state created the Primary Care Payment Reform Collaborative to study primary care spending and issue recommendations. State Bill 934 in 2017 required Oregon’s Coordinated Care Organizations and plans for public employees and educators to spend at least 12% of their total budget on primary care by January 2023. The state has impressive public-facing Oregon Primary Care Spending Dashboards that report the overall primary care spending rate for primary care at or above 13% of total medical spending for all lines of business (e.g., commercial, Medicaid, Medicare Advantage). The Oregon report cards show not only primary care spending as a percentage of total spending by plan type, but also the extent of non-claims spending on primary care and primary care spending by plan. Oregon also has a cost growth target program that sets a 3.4% cap on cost growth for most payers. The overall cost growth targets ensures that increased investment in primary care will not be inflationary.

- Oklahoma focuses its primary care investment actions on Medicaid spending. SB 563 directs the Oklahoma Health Care Authority to transition Medicaid from FFS to managed care and requires that 11% of spending to be spent on primary care by its Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) no later than the fourth year of a contract with the Medicaid program.

- Rhode Island was the first state to adopt policies to increase primary care spending through its 2010 affordability standards, requiring commercial insurers to increase the share of health care spending allocated to primary care by 1% annually, while hospital price growth was capped at the Medicare price index plus 1%. The state required corrective action plans for meeting the primary care investment targets and included an enforcement mechanism to motivate improvement. Primary care spending subsequently increased, while total spending slowed, driven by hospital price growth caps. By 2018, 12.3% of spending by commercial insurers went to primary care, though upon further exploration the state found that the definition of primary care spending was overly broad and revised the definition to be narrower to address the root challenges for primary care. The new, narrower definition became effective beginning September 2024 and is set at a 10% target primary care spending of total medical spending.[9]

- Washington State’s primary care investment target, set by legislation (SB 5589), is set at reaching 12% of total healthcare spending on primary care. An advisory committee is working to define measures, track progress, and recommend strategies for payers (insurers, state plans) to meet this goal, aiming to shift away from fee-for-service towards team-based care. Current spending is significantly lower (around 6%), highlighting the need for increased investment, with some suggesting annual increases of 1-2%. The target is not enforceable and does not have a statutory enforcement mechanism (such as financial penalties or fines for non-compliance) for payers that fail to meet the goal. Instead, the state relies on voluntary measures, public reporting, and monitoring through the Health Care Cost Transparency Board.

Among the states with bills introduced or other proposed state actions to increase investment in primary care:

- Colorado’s HB19-1233 established a Primary Care Payment Reform Collaborative that started meeting in July 2019 and has been extended until 2032. The Collaborative’s work includes measuring the percent of medical spending by plan. The legislation also requires commercial insurers to increase primary care spending by 1% in 2022 and another percent in 2023 and insurers are prohibited from raising premiums to cover the increased spending on primary care. The Collaborative uses Center for Improving Value in Health Care (CIVHC) Colorado data to track changes in primary care investment over time. They found that primary care spending across all reporting payer types has increased from 14.8% in 2022 to 15.7% in 2024, though it is uneven among payer types.

- In 2021, Hawaii required Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) to report on and increase the percentage of medical expenditure devoted to primary care. This did not result in increased primary care spending due to pandemic-driven pressures and other challenges. However, Hawaii is an AHEAD state and this will increase primary care funding for participating practices. In addition, Hawaii’s SB1646 introduced in 2025 requires the Hawaii Employer-Union Health Benefits Trust Fund Board of Trustees to negotiate with health insurance carriers to ensure that 12% of monthly premium payments are paid directly to primary care providers.

- In the fall of 2007, the Maine Legislature convened the Commission to Study Primary Care Practice to examine the issues facing primary care and ways to stabilize and support it. In the 2008-2009 State Health Plan, the Governor’s Office for Health Policy and Finance identified the need to promote primary care as the foundation for the state’s health system. The Maine Quality Forum issues annual reports, pursuant to Public Law 2019, Chapter 244. The most recent (November 20, 2025) report found that in the most recent year of reporting, 2023, primary care spending as a percentage of total payments was highest for MaineCare (11.6-12.7%), followed by Medicare (9.6%) and commercial payors (7.6%).

- Maryland has a history of success in supporting primary care practices often paired with or as a part of larger reform efforts. For example, the state entered into a Total Cost of Care Model with the Federal Government designed to coordinate care for patients across both hospital and non-hospital settings, improve health outcomes, and constrain the growth of health care costs. A key element of the model was the Maryland Primary Care Program (MDPCP), a voluntary program open to all qualifying Maryland primary care providers that provides funding and support for the delivery of advanced primary care throughout the state. The model is comprehensive and offers pharmacist, health and nutrition counseling, behavioral health, coordinated referrals and linkages to social services and support from health educators and community health workers to provide an integrated experience for patients. The state uses Care Transformation Organizations (CTOs) to allow practices to avail themselves of these resources without the need for direct investment. Public reporting has demonstrated that the MDPCP has contributed to decreases in Medicare total expenditures, as well as decreases in inpatient and emergency room utilization, all while maintaining budget neutrality. In addition to the MDPCP, Maryland will begin its implementation of AHEAD in January 2026 at which point MDPCP will become part of AHEAD in Maryland.

- In December of 2025, the Massachusetts Primary Care Access, Delivery, and Payment Task Force released its first report, which recommended that a target for spending on primary care in Massachusetts be set at 15% of total healthcare spending, or double the current primary care spending share, whichever is greater, within five years of 2026. The Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association has released a statement saying that “Primary care is our most powerful tool for building healthier communities, easing the burdens on emergency rooms and caregivers, and connecting patients with the personalized services they need. We commend state leaders for giving primary care the close attention it deserves.” However, they also caution that a spending target would need to “be implemented in a meaningful, pragmatic, and collaborative manner – especially within the context of the growing pressures and current investments that exist within today’s delivery system.”

As well, MassHealth, the state’s combined Medicaid and CHIP program, introduced primary care subcapitation for providers participating in MassHealth’s Accountable Care Organizations. This has increased investment in primary care[10] and is an example of how states can use Medicaid in strategies to better fund primary care.

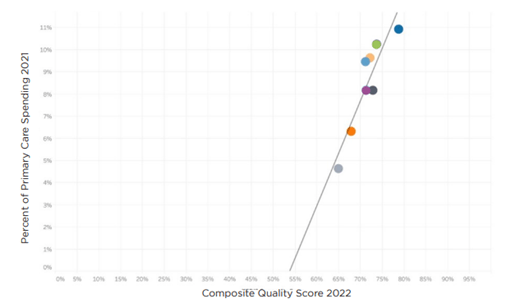

In addition to efforts to advance primary care investment in Massachusetts, a recent analysis of the eight largest provider organizations in Massachusetts found that provider organizations with high primary care investment as a percent of total spending performed significantly better on standardized measures than those with lower primary care investments as shown below.

Primary Care Spending and Quality in Massachusetts

Note: The linear regression produced an R-squared value of .84 and a P-value of .001

Source: Analysis of Massachusetts: Primary Care Investment and Quality, Freedman Healthcare, July 2024

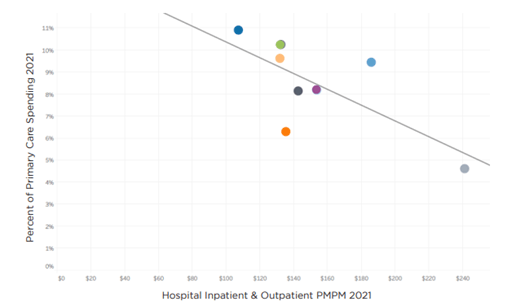

The study also assessed the relationship between spending on primary care and hospital spending for the eight organizations and found that those with higher investment in primary care experienced lower hospital spending as shown below. Though the predictive values were lower than in the quality analysis above, the findings illustrate the potential for primary care to stem avoidable inpatient care and emergency room visits.

Primary Care and Hospital Spending in Massachusetts

The linear regression produced an R-squared value of .50 and a P-value of .05

Source: Analysis of Massachusetts: Primary Care Investment and Quality, Freedman Healthcare, July 2024

- New Jersey requires Medicaid Managed Care Organizations to report the percentage of total medical expenditures devoted to primary care, as well as the State Department of Pension and Benefits to report on primary care spending for state-run health plans, such as the state employees’ plan. Though there is no statuary primary care spending target, a 2021 executive order set benchmarks for limiting overall health care cost growth, with targets of 3.2% for 2024 and 3.0% for 2025. The 2026 HealthCare Cost Growth Benchmark Report released in January 2026 by the state shows that statewide per person per year total health care expenditures increased by 6.1% between 2022 and 2023, exceeding the cost growth benchmark target of 3.5 % by 2.6 %. The report also includes per person spending by submarket for primary care spending, which shows a small increase from 2022 to 2023, the most recent data year available.

- In New York, Senate Bill S1634 would require health plans and payers to have a minimum of 12.5% of total medical expenditures on physical and mental health spending be spent on primary care services. The bill was introduced for the 2025-2026 legislative session, passed the New York State Senate, and is pending consideration by the State Assembly.

- North Carolina established a Primary Care Payment Reform Task Force (S. 259) in 2023 to define primary care, assess current spending and issue recommendations. The goal is to establish a primary care investment target, with the goal of increasing investment to improve health outcomes and control costs, following national trends for 12-15% benchmarks.

- Utah has a Primary Care Spend Project operated within the Utah Department of Health’s Office of Health Care Statistics, which uses all payer claims data to calculate the total amount of spending on primary care as a percent of total medical expenditures. The 2023 report shows CHIP primary care spending at 9.5% for 2022 using a narrow definition of primary care spending, and 6.2% for commercial payers.

- Vermont passed legislation in 2019 requiring the Green Mountain Care Board (GMCB) and the Department of Vermont Health Access (DVHA) to define primary care, measure spending, and develop methods to increase primary care investment, aiming for at least 12% of total healthcare spending, with goals to align Medicaid rates with Medicare, though there is not an enforcement mechanism. Additionally, the dissolution of a major health plan (OneCare Vermont) has challenged progress. Legislation has been introduced in the House and Senate however that is now under consideration that would set a target in state law that 15% of total health care spending in Vermont go to primary care, with the Vermont Medical Association encouraging passage.

There are four key lessons that can be drawn from the composite of efforts across the many states addressing increasing investment in primary care .

- Primary Care is In Crisis – The sheer quantity of states with initiatives to increase investment in primary care reflects concern about the primary care crisis nationwide. States are taking action to increase the percentage of spending that flows to primary care through legislation, rate review, state employee plan provisions and voluntary payer and purchaser-based initiatives to bolster the primary care infrastructure that patients depend upon.

- Definitions and Approaches Matter – The way that primary care investment is defined is important so that increased investment accomplishes better care for patients. Similarly, the approach and approach to increased investment help to orient provider behavior. There is merit in both the narrow definition of primary care spending (spending that flows to primary care physicians) so that team-based care can be resourced, but there is also merit in assessing the broader definition of primary care spending and the important roles that behavioral health and advanced practice providers play in whole-person care. It is also clear that Advanced Primary Care is gaining ground and will be the new north star for care delivery over time.

- Measurement Alone Doesn’t Do the Job – Measurement alone is important but insufficient. It is difficult to command attention and action to increase primary care investment without a penalty or consequence for non-compliance. Unsurprisingly, the data also illustrates that efforts with consequences for not meeting targets are the most effective at achieving the aim of increasing investment in primary care. Some states have financial penalties for health plans who do not meet incremental primary care target spending levels. Others require corrective action plans. Some use rate review as a way to enforce compliance with primary care spending targets. Products subject to rate review would be subject to meeting the incremental target for full approval.

- Increasing Investment in Primary Care is a Team Sport – In achieving a primary care spending target, employers, labor groups, trusts, and other purchasers are important stakeholders as state legislation applies only to fully-insured products and not to those who are self-insured and ERISA-exempt. However, self-insured groups can voluntarily replicate these provisions in their self-insured coverage designs, and leading purchasers across the nation have already started to incorporate increased investment in advanced primary care in their benefit designs.

- [1] Foubister V. Five States Leading Efforts to Increase Primary Care Spending. The Milbank Memorial Fund. March 12, 2025

- [2] https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/Physical_distress/MI

- [3] https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/InvestingPrimaryCareWhyItMattersCommercialCoverage.pdf

- [4] B. Starfield, et. al., Contribution of Primary Care to Health Systems and Health, Milbank Quarterly, 2005 Sep;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

- [5] Implementing High-Quality Primary Care, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Implementing High-Quality Primary Care; Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2021 May 4. ISBN-13: 978-0-309-68510-8ISBN-10: 0-309-68510-9

- [6] https://hcai.ca.gov/affordability/ohca/promote-high-value-system-performance/primary-care-investment-benchmark/

- [7] https://legis.delaware.gov/BillDetail/68714

- [8] https://dhss.delaware.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2025/02/pcrcstrategicplanrpt24.pdf

- [9] https://www.milbank.org/publications/states-lead-efforts-to-increase-primary-care-spending/#:~:text=OHIC%20also%20plans%20to%20implement,’%E2%80%9D

- [10] https://www.chcs.org/resource/massachusetts-primary-care-sub-capitation-model-implementing-primary-care-population-based-payment-in-medicaid/

Your Chance to Vote: PO and Practice Michigan Primary Care Survey

We would love your perspective! Whether you represent a primary care practice or Physician Organization in Michigan, please respond to the QR code below to let us know your experience with the following questions:

- Do you represent a Physician Organization or a primary care practice perspective?

- a. Physician Organization

- b. Primary Care Practice

- c. Other

- How important is it for health plans and payers to use common payment approaches in contracts?

- a. Very

- b. Somewhat

- c. Not at all

- How important is it for health plans and payers to use common incentive metrics and requirements (e.g., patient minimums, definitions, etc.)?

- a. Very

- b. Somewhat

- c. Not at all

- Are your practices working toward or have they implemented the advanced primary care model?

- a. Have already implemented

- b. Are working toward implementation

- c. Are not interested in implementing

- If not interested in implementing the advanced primary care model, or encountering challenges, what are the barriers? (e.g., lack of care manager or physician champion, lack of ancillary or administrative support, retiring soon, etc.)

- What percent of your total payments have two-sided risk (i.e., some element of both gain and loss sharing)?

- a. 0% (no payments have two-sided risk)

- b. Less than 10%

- c. More than 10% but less than 20%

- d. More than 20% but less than 30%

- e. More than 30%

- How prepared do you feel for two-sided risk?

- a. Very prepared

- b. Somewhat prepared

- c. Not at all prepared

- If not prepared for two-sided risk, what barriers are you encountering?

Primary Care Investment Guide

This month, our feature selection of our February-March Journal Club releases of The Primary Care Investment Guide and its companion Executive Summary are a great step forward for policymakers, employers, provider organization leadership, practices and health plans to better understand how they make strategic investments in primary care and advanced primary care management.

The authors, a nationally-recognized set of prominent researchers from Harvard, UCSF, Oregon Health and Science, and Suffolk assess the body of literature and highlight six team-based services that improve health outcomes, reduce costs, enhance patient experience, support workforce wellbeing and advance equity:

Behavioral Health Integration, including the Primary Care Behavioral Health model and the Collaborative Care Model

- Embedded Clinical Pharmacists to optimize medication management and chronic disease control

- Care Management for patients with complex medical or social needs

- Population Health Programs that use data to close care gaps and proactively manage chronic disease

- Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) and Disparities Initiatives, including systematic screening and community health worker support

- E-Consults, enabling rapid, specialist input and reducing avoidable referrals

The guide is a big step forward in both understanding more about high value team-based care components and how to best resource them for success.